|

Chapter 1

"Cargo"

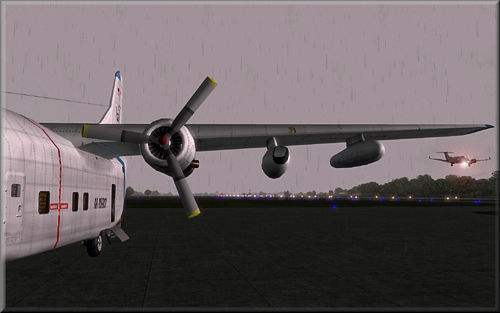

The guy’s late – again! He’s always late. Along with the

co-pilot and our line chief I stood quietly in the aft

bay looking out through the open cargo door. We watched

the light rain make circles in the puddles on the

concrete apron. The daylight is fading quickly. The big

ramp lights up on the poles are on already, but aren’t

yet adding much to the natural daylight remaining. That

will change in a few minutes as the real dark creeps in.

I look again at my watch, for maybe the hundredth time

in the last half-hour as I watch a King Air touch down.

He’d just appeared out of the goo a mile or so out at

about a thousand feet AGL and made a nice final approach

on to 36. Not at minimums for the ILS, or even near it,

but still enough to keep you on your toes. Nice work,

buddy. Too bad you’re not who we’re waiting for.

It’ll be fully dark by the time we finish loading and

launch now, even if our delinquent driver were to show

at this very minute. Earlier, I’d hoped for a bit of

daylight for our climb out, but it’s not in the cards

tonight. That door closed for us about an hour ago.

We’re waiting for the last of our cargo, the bulk of it,

really. This run would barely pay for the gas without

what’s still coming – hopefully still coming, that is.

He’ll show, of course, I think sarcastically. He always

does, sometimes an hour or more late, and with another

nearly incredible cockamamie story about why he wasn’t

here when promised. Oh, he’ll show, but there are times

I wish he wouldn’t.

And so we wait, not talking much, the three of us, under

the overhanging aft end of the hulking old C-123. The

line chief, Charlie, is a piece of work. He pretty much

runs the ground operation here at Ocala; managing the

aircraft maintenance, the warehousing, the loading and

unloading of the aircraft and the trucks that come and

go, the logistics, why he even has his hand in making

the office end of things run smoothly, though my wife

would never admit it. He doesn’t look the part. Fifty-ish,

balding, a little paunchy, and very deliberate. He has

the habit of stopping to consider what he’s about to say

before he says it. That’s an unusual quality, if that’s

the right word. If you ask him a question, he cocks his

head a little to one side, gets that thousand-yard-stare

going for a second or two, and then delivers what is

usually a reasonably accurate answer.

Joe, the co-pilot is quiet too; he’s always that way.

He’s young and reasonably competent, but just isn’t the

gabby type, not by half. Joe’s just a kid really, with a

commercial, multi-engine ticket, no military experience,

a year and a half out of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical

University. He wasn’t picked up by the airlines

immediately out of school, so he took a job with us to

build hours and gain some real-world flying experience.

He’s got type ratings in all our aircraft now, including

the Provider, so he gets plenty of hours. I don’t expect

him to stay around much longer. I’m pretty sure he’s

scratching at the door of the air carriers’ Personnel

departments - - - excuse me, Human Resources departments

- - - regularly, but that’s his prerogative, I guess.

I know Joe prefers flying the right seat of our jets, or

one of our lighter turboprops, but he drew the short

straw to co-pilot for me tonight. He’s stuck with me and

the C-123’s thundering, vibrating, oil-leaking Pratt &

Whitney R-2800s for this flight, and I’m stuck with him.

I can’t help but wonder who got the worst of the

bargain. Him, I guess. Apart from his inability to fill

a silence, uncomfortable or otherwise, there’s little to

fault. His flying’s OK, he does what he’s told, and

sometimes a little more. Tonight’s an example. He

doesn’t have to help load the aircraft, but he will.

Charlie sent the rest of the ramp guys home a half hour

ago at their scheduled time, even though we still had

cargo coming. Ours is the only flight scheduled until

early tomorrow morning. Charlie hates guys standing

around drawing overtime almost as much as my wife does,

and she’s paying the bills.

“Joe,” I address the co-pilot, “when he shows up, maybe

you’d better go on in and dial up the Flight Service

Station and have them set our flight plan back by

however much it’s slipped. His stuff is palletized, so

we can load it, run the weight and balance and be ready

to go in, oh, say fifty minutes from the time he hauls

his sorry ass in here.” Joe just nods. I smile inwardly

just a little, knowing that I’ve just caused him to have

to actually talk to somebody, even if it’s not me.

To be fair, Joe does talk whenever it’s required. He

handles the radios when we fly, for instance and does it

well. He’ll read a check list aloud, or respond when I’m

reading one. Not an extra word, mind you, but he does

talk from time to time.

Charlie asks about fuel. We don’t know our final payload

weight yet, and the flight is a medium-long one. There

are about 5,700 lbs. of fuel aboard and the planning

sheets I’d looked at earlier said that would be enough

to cover the flight plus the required reserves. I like

to have more than enough though, and Charlie knows my

habits. “We don’t know for sure how much cargo he’s

bringing, so until we see his load sheet, we won’t know

our gross”, I answer. “It’s going to be close, but we

may have room for a few hundred pounds more. We’ll just

have to see where we are when the dust settles. If

there’s room to add some gas we’ll do it after we’ve

finished loading.” I didn’t want to guess now and end up

overweight. This thing’s enough to haul off at max gross

and I won’t overload her. I surely don’t want to add

fuel now and end up having to pump some of it out later

to get back legal.

Charlie gets the thousand-yard stare in his eyes for a

second, then nods and makes a non-committal noise in his

throat.

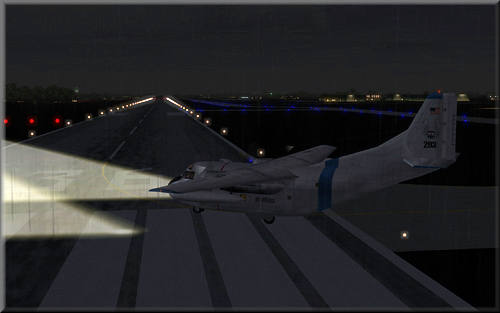

We’re headed North tonight, as most of our flights out

of Ocala do. You can’t go too much further South from

here, unless it’s to be an international run. We’re

bound for KLCK, Rickenbacker, on the South side of

Columbus, Ohio, about 700 nautical miles. We’ll be

loaded heavy and making a night landing as well. Not a

milk run, but it shouldn’t be a problem if we just do

things by the numbers. Rickenbacker is a former military

field, now a mixed use facility with civilian

enterprises sharing the turf with an Ohio Air National

Guard squadron. It’s mainly a cargo terminal serving

central Ohio. It has good navaids, nice big runways and

ample ramp space, which we won’t even make a dent in.

There’s not much in the way of air carrier traffic

there, but lots of big jets without passenger windows,

if you get my meaning. It’s the kind of place an old

freight dog loves – the only thing missing is radial

engines, and we’ll be bringing our own.

After staring for what seemed hours with my mind

wandering, I noticed with a start that our wayward truck

had just pulled up to the gate in the fence. “There he

is.”, I said to the others, unnecessarily. Joe started

toward the office, predictably without a word. Charlie

muttered, “About damn time!”

Charlie stepped off the end of the ramp and headed over

to direct the truck driver where to park. This guy was

well known to us and Charlie wanted to make sure that he

didn’t get a chance to use our airplane to dent his

truck, a not entirely implausible possibility for this

character. We’d use a lift truck to ferry the pallets of

cargo from the truck to the plane, and a hundred extra

feet wouldn’t make much of a difference.

I stepped down, and headed for the driver, who was

coming toward me on foot waving a clipboard, Charlie

trailing along behind looking a little disgusted.

“There’s more than we thought” the driver said with a

half-shrug that hinted embarrassment. “I had to wait for

the shipping guys to get the last of it boxed up and

palletized, that’s why I’m late. You know how those

shipping department guys can be.”

“And how much extra is there?”

“Well, it says right here…” He shuffled through the

sheets on the board and squinted his eyes to read the

fuzzy 5th daughter of an NCR original under the harsh

ramp lights. “…there’s twenty-six hundred pounds more,

almost. Twelve thousand, seven fifty total.”

This was not good news. I ignored him as I did some

quick mental arithmetic. We already had some six

thousand pounds of mail aboard. That was going to fly,

no matter what. It’s a government contract, hard to get,

easy to lose and oh-so-profitable, though not enough in

itself to make this flight a paying proposition in this

aircraft. Given that, I had serious doubts we were going

to be able to accommodate all of this additional cargo.

I’d have to run the numbers to be sure, but it was going

to be tight at best. I had a moment to recall with

satisfaction that I’d held off on loading that extra

fuel. Good thing.

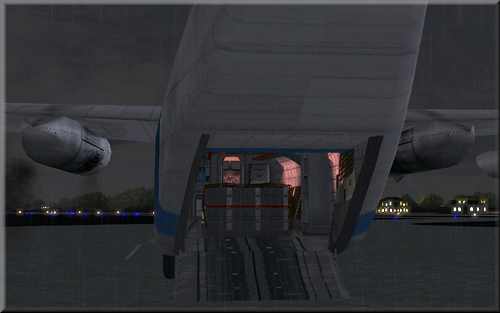

Three quarters of an hour later the pallets, were

loaded, secured and netted - all that were flying

tonight, that is - and we were bidding a not-so-fond

adieu to our truck driving friend. “He wasn’t happy

about only part of it going.” Charlie observed, as the

truck headed for the airport gate.

“No, he wasn’t, was he? They told the office this

morning they’d have just over ten thousand pounds for

us. That’s what we planned for. If we’d known, we might

have made other arrangements for some of that mail, or

scheduled a bigger plane, but it’s too late to lay on

another flight tonight. He and his boss are just going

to have to live with the fact that we can’t take all of

it in this load.”

I thought for the moment about our customer, the wayward

driver’s employer. They were a medium sized local

manufacturing firm, making of all things, tail light

assemblies for all sorts for trailers. It was a niche

business, but apparently a prosperous one, judging by

the amount of stuff that they shipped by air. They were

a good customer, at least from a revenue point of view,

one we’d hate to lose. The bad news was that they were a

bit disorganized most of the time and they often ended

up being the tail that tried to wag our dog. The chronic

late deliveries were examples; ditto the ton plus of

extra payload they’d dropped on us without warning.

Finishing the thought aloud, I told Charlie, “First

thing in the morning you’ll have to get the office

looking at what to do with the part of the cargo we

couldn’t take.” Charlie had already fork-lifted the four

pallets that would have put us over our maximum gross

weight into the warehouse.

“OK”, he responded. “The boss won’t be happy though.”

“No, she won’t”, I agreed.

He referred, of course, to my wife. She was the love of

my life, and, coincidentally, the president and CEO of

our little air freight business. Not so little any more,

I reflected. Though we’d started small and did our share

of struggling, we’d finally achieved a measure of

success. Not that the Board of Directors of UPS were

losing any sleep over us, but still, not too bad. We had

leased freight terminals at over a dozen airports in the

Southeast and Mid-west and operated a fleet of nearly 20

aircraft. Most were tired 727s and 737s, plus a handful

of Caravans and an almost new Beech 1900 that we managed

to pick up at a once-in-a-lifetime price…and our trusty

old Fairchild C-123. The Provider was my pride and joy,

but a burden to bear for almost everyone else in our

company.

The fact that we have that plane at all is, pure and

simple, a case of my wife indulging me. We both pretend

it’s a good business decision to own and operate the

forty year old relic, but we both know that it’s pretty

much a break-even situation most months. She doesn’t rub

my face in it and I work hard to make it as much a

revenue generator as possible, but we both know. Even

when it makes money, it’s still a burden as it is so old

and so different from everything else we fly. Its

capacity and range do fit a gap in our other

capabilities however, and the huge aft loading ramp

offers a definite advantage over even the cavernous

Boeings when there’s a vehicle or other bulky freight

involved. Occasionally this beast is just the right tool

for the job.

Thus my flight tonight. This morning, the cargo headed

for Ohio had looked like a custom fit for the old

Provider. The mail plus the trailer lights shipment

would make, at that range, a near-perfect load. Rather

than send it in a half-empty Boeing we scheduled the hop

for me and my aluminum pacifier. All looked good until

the extra 2,600 pounds of cargo darkened our door less

than an hour ago. Charlie was right, she wouldn’t be

happy in the morning, and I’d already be in Ohio.

Sometimes, things just work out. Life is good.

End – Chapter 1

Click on

logo to download chapter 1 as pdf |