|

January 2008

|

|

|

Lockheed P-38J late model |

Introduction

I've been an aviation buff from the time I was old

enough to notice airplanes. As a child, any ride in the

car would include a detour past the airport if Dad could

be persuaded; Dad was plane-crazy too, so it never took

much to convince him. During all the considerable

intervening span of time, my favorite airplane, bar

none, has been the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. There's just

something about it that I've always found captivating.

I've been fortunate enough to have seen the P-38 fly at

air shows four or five times. They were always uncommon

in the postwar years and are becoming increasingly rare.

Only a handful of airframes still exist and only a few

of those are flyable. Those that can still fly are flown

carefully and infrequently compared to more common

warbird types.

You can imagine then, my excitement when Just Flight

announced the impending release of their P-38 package. I

managed to acquire one very quickly after it became

available.

The Aircraft

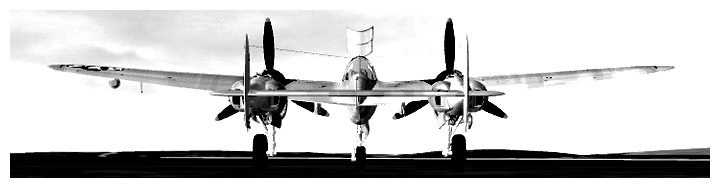

The P-38 is unique. The configuration is unusual and

easily recognizable; it was considered quite

unconventional at the time it was conceived. The

Lightning was designed to meet a US Army Air Corps

requirement for a high-speed, high-altitude interceptor

in the late pre-war years. Originally named Atlanta

(after the god, not the city) by Lockheed, the RAF

re-christened their early P-38s Lightning and that's the

name that stuck.

Designed by Lockheed's famous Kelly Johnson, the

aircraft incorporates some innovative technologies and

was ahead of its day in several respects. Tricycle

landing gear, counter-rotating engines, turbo-chargers

versus the more common engine-driven superchargers and

centreline-mounted guns (including a cannon) were all

unusual for that time. So too was the twin-engine,

single-pilot layout.

Even though the prototype crashed at the end of a very

long demonstration flight, the Lightning met the Army’s

challenging acceptance criteria and was soon put into

high-volume production as the US entry into the war

approached. Though reasonably capable, it soon acquired

a chequered reputation due to technical faults, some

with the airplane itself, some resulting from the

training that was being provided, and some with the

support services that were available, especially fuel

quality.

Considered a mediocre performer as a long-range escort

fighter in the European Theatre of Operations, it was

supplanted in that role by the P-51 Mustang as that

superb aircraft became available. After being largely

displaced as a bomber escort the Lightning was employed

in the ETO primarily for ground attack and

photo-reconnaissance, where specialized variants

performed admirably in both roles.

The story in the Pacific was quite different. Though the

technical faults were known and the training was the

same, the attitude toward the P-38 was very different

from that in Europe. Differences in climate, geography,

and the tactical situation in that region, coupled with

the availability of better quality fuel, combined to

enhance the strengths of the P-38 and minimize its

faults, real and perceived. America's two top scoring

WWII aces, Bong and McGuire, both achieved their record

of victories entirely with the P-38 in the Pacific

Theatre of Operations.

From the J-model onward, the Lightning's technical

problems were largely a thing of the past. Small,

quick-acting dive recovery flaps had solved the

compressibility problem in high-speed dives;

hydraulically-boosted ailerons greatly increased

roll-rate and correspondingly reduced control forces; a

new turbo-charger intercooler arrangement resolved

problems that had earlier led to frequent engine

failures. The late J-model and all of the L-models of

the P-38 (there was only 1 K model) proved to be

superbly capable, effective and reliable. About 11,000

Lightning's were built; nearly 7,000 were of the

definitive J- and L-models.

The Software

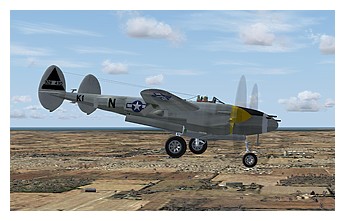

Created by Aeroplane Heaven and published by Just

Flight, this eagerly awaited package lives up to

expectations. Supplied in five variants (including the

F4 and F5 photo reconnaissance types but not the

ultimate L model) in seventeen paint schemes, everyone

should find one that pleases them. The external models

are accurate and detailed.

The JF/AH P-38 package is compatible with both in FS9

and FSX. All my flying with it has been in FS9.

The first thing you notice about this package is that

there is no 2-D cockpit provided. When starting you

begin in 2-D mode with an unrestricted forward view;

there’s no part of the aircraft in the view. One press

of the W key brings up a set of seven instruments at the

screen’s bottom edge. These include five of the six

basic flight instruments, but oddly, no gyro compass.

The remaining two are a dual-indicating fuel gauge and

an instrument depicting landing gear and flap positions.

All seven are genuine period-style gauges, not the

FS/Cessna gauges that normally appear here in W-key

view. Though the aircraft can be flown from this view,

it’s a very unsatisfying experience – why would you want

to?

|

|

|

To quote Elmer Fudd, “Th..th..that’s all,

folks!” |

The Cockpit

So, on to the 3-D cockpit – it’s not as if there’s much

choice. I’m not an expert on 3-D cockpits; I normally

fly the 2-D. This is my first experience spending any

significant amount of time in the 3-D office of any

aircraft. Because of that, I don’t feel particularly

qualified to comment on whether the implementation of

this one is good or bad in comparison to other products.

What I can say is that the cockpit appears to be

authentic – and accuracy appears to have been a primary

criterion for the developers of this package.

The cockpits look and feel right to me and they work.

The authors of this software have gone out of their way

to avoid any hint of a gamey look and feel. For

instance, there are none of the familiar sim-icons

anywhere. The radio and GPS (the hand-held Garmin) can

be accessed via top-line menu pull-downs (or Shft-2 and

Shft-3), as can the ATC window, but you won’t find any

visible controls for anything that wasn’t put there by

Lockheed or the Army.

|

|

|

Vintage panel |

The radios are vintage, as are all the instruments.

Looking for an HSI, or an OBI or a glide slope? Forget

it, Mac, this is 1944. They haven’t been invented yet.

|

|

|

Transistors won’t be invented for another 20

years or so |

The manual and advertising copy for this package

indicate that the 3-D cockpits are very authentic, and

that the aircraft can be flown “by the numbers” from the

3-D view, including cold starts. This would seem to be

the case. I couldn’t identify anything important that

was missing or that didn’t work. It is necessary,

however, to become familiar with the eye-point controls

for leaning left, right, forward, etc. As must be true

of the real aircraft, you can’t just sit immobile in a

central position and expect to see and reach everything.

Oh, for a TrackIR!

The Lightning has a yoke, not the more common stick.

There’s a deck-mounted pylon on the right side of the

cockpit. At its top, a bar extends horizontally to the

left over the pilot’s legs and it’s on this that the

wheel is mounted. That horizontal bar also carries a

handful of switches and controls. Pitch inputs move the

entire pylon fore and aft through its pivot point at the

deck.

|

|

|

No stick here… |

There’s quite a lot of variation from model to model in

the panels, equipment and layouts. For instance, both

the J-model combat variants have a huge, hulking, gun

sight and also an extra horizontal frame member at the

bottom edge of the windscreen that blocks a good part of

the forward view. The F5 photo-reconnaissance model has

the frame but not the gun sight. Neither the F combat

model nor the F4 photo-ship have either the sight or the

extra frame member. Forward visibility from them is

considerably better.

In the later models the magnetic compass protrudes from

the panel and masks most of the altimeter, situated just

below it. Most of the altimeter face can be viewed by

leaning forward and left but it’s awkward and

inconvenient, particularly during approaches.

Flying the Lightning

Ground handling is relatively easy. The nose gear

steering is crisp and precise. Even in the models fitted

with the Sight, gun, massive, aviation, view-blocking,

Army, Mark I, Mod 3, the obstructed area of view is

narrow. It’s easy to see both edges of the taxiways and

any impending turnoffs well ahead without swivelling the

view.

|

|

|

Ground view |

The engine sound is very good – the suggestion of muted

power is there, but if you’re used to flying Merlins,

it’s not like that at all. Instead of eight-inch long

exhaust stacks, the Allison’s exhausts are routed aft

through the booms to the turbo-chargers on the top of

each, almost as far back as the trailing edge of the

wings. The turbochargers and exhaust plumbing are fairly

effective mufflers and there’s none of that burbling,

barking exhaust noise. You won’t mistake it for a Cessna

however, nor for a radial. Other sounds, flaps, landing

gear, wheel noises and such also seem about right.

When you’re lined up to go and push the throttles,

you’ll experience something unique for a

high-performance propeller AC – or rather you won’t

experience it. There’s no torque, thanks to those

counter-rotating engines. It tracks dead straight, just

goes where you point it, even with the reality sliders

all the way up. If there’s no wind you can take off

without touching the rudder pedals, as long as you’ve

lined up well. It’s one of the things that pilots loved

about the Lightning.

The P-38 with full fuel (including the drop tanks that

are included on every model) is a heavy airplane and it

doesn’t exactly leap off the ground in 1,000 feet.

Maximum weight is on the far side of 20,000 lbs and even

with no weapon load you can expect to be above 16,000

with all the tanks full. Once off and the gear

retracted, initial climb is breath-taking for a piston

engine aircraft. You can exceed 4,000 fpm for a minute

or two, though you soon run out of steam and have to

lower the nose.

|

|

|

Off we go, into the wild blue yonder… |

Engine management is important in all phases of flight.

The throttles and manifold pressure gauges are the

primary tools for this; there’s no separate boost

control. At low and intermediate altitude, there’s

enough throttle to easily over-boost the engines, so

keeping one eye on the MP is important when making

changes. Mixture control is, of course, important as

well.

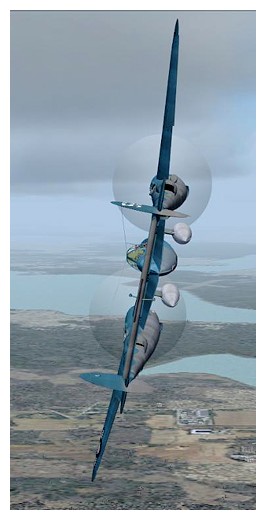

The Lightning is an agile and well-behaved aircraft.

Manoeuvrability is quite good, considering the size and

weight. There’s ample power, but energy management is

necessary. High-g manoeuvres eat away at the airspeed and

can’t be maintained indefinitely. Turn rate is

phenomenal; put the lift line through where you want to

go and pull hard, but watch the airspeed. Roll rate is

good, but not stunning.

|

This aircraft doesn’t seem to have any bad habits. Stall

recovery is easy and conventional.

The AC must be

bullied into a spin and once in it, recovery is nothing

unusual – lower the nose, reduce power, kick opposite

rudder and you’re flying again.

Bearing in mind I’m not a 3-D guy, I found landings a

challenge.

The P-38 is easy to land – it’s difficult to

land well. Forward visibility is OK with some flaps out

to pitch it down a little, but too much of a good thing

causes problems.

With full flaps the AC will pitch down

a lot. That coupled with the long nose strut means you

have to really haul hard to get the nose high enough in

the flare to touch down on the mains.

I wheel-barrowed

more than one landing and soon learned that two notches

of flap was about all that was easily manageable.

Approach, touchdown and stall speeds are all comfortably

low and long runways are not needed if the approach is

flown reasonably well. |

|

Yanking and banking |

|

|

|

|

|

Full flaps approach |

No Wheelbarrow

here |

In flight, the magnetic compass is “noisy”, just as in

the RW. In every FS aircraft I’ve ever flown, the

magnetic compass is steady as a rock. That’s just not so

in the real world, where you’re taught to only trust it

in “…straight, level, un-accelerated flight”. Someone

took the time to make this one behave realistically, the

first time I’ve seen that.

There’s no index needle on gyro compass. Fly a heading

of 133 degrees? Well somewhere between 120 and 150 ought

to be about right…

Summary

This is a great package modelling a great airplane. Its

immense fun to fly in its own rite, but all the more so

if you have some appreciation for the history of it.

The appearance is excellent. The credit for that has to

be shared between Airplane Heaven and Lockheed, though.

I never get tired of looking at it.

|

|

|

There’s nothing else like it! |

The external models are quite good and that broad range

of paint schemes, including some nose art, add to the

effect. For some reason, though, the nose art only

appears on the port side. The animations, including an

opened gun bay, are very good. Engine starting has those

counter-rotating propellers cranking correctly, outboard

at the top, and you see the blade pitch adjust just

before they start to turn over. There was a lot of

attention to detail in this production – no doubt a lot

of it escaped me, but I’ll find most of it sooner or

later. I’m certainly not done flying this thing, not

while there’s breath in me.

|

|

|

Bong’s “Marge”, gun bay open |

This is a very well-done,

very pleasing piece of software. It is clearly intended

to be long on authenticity, on fidelity to the original

aircraft. This appeals to a certain kind of sim pilot.

This is not the sort of aircraft you’ll make long IFR

flights with, though many brave young men, now old or

gone, did that during the war. It’s not likely to be a

good Cargo Pilot airplane or one you’ll buy for your VA.

This package was intended for the aficionado, the

warbird buff, the history lover, the guy who values

realism above convenience

– in a word, for me! Thanks, JF and AH. I love it!

John Allard

|